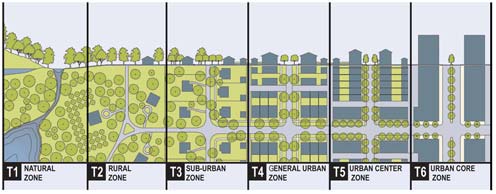

My treasured colleague and mentor, Bill Fulton, is creating our brave new post-pandemic world’s econ dev model that is a dramatic shift in how we are socializing into the mid-21st century. You can find his writings about his approach on his Substack page. He’s clearly identified and defined the patterns within the urban core/center and general urban areas and I’ve merely added the rural component to complete the ‘transect’ of econ dev place types.

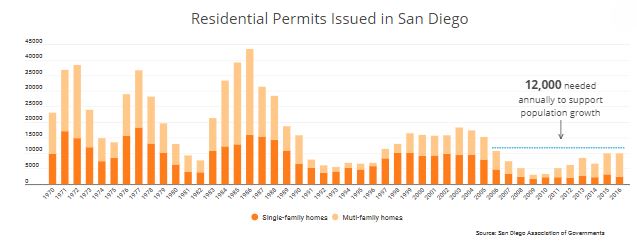

Our state-by-state policy shift towards mixed-use, walkable urbanism is finally complete. Every city across the nation has general or comprehensive plan policy that allows for urban infill development. But this process has taken 30 years and the promised transit to support this new urbanism hasn’t been funded, and now we are in a new socializing era. We didn’t plan for the unintended consequences of a global pandemic… that low-density, auto-oriented, suburban homes would become mixed-use, live-work buildings.

We didn’t plan for urban downtowns to have less work and less shopping after building more housing. We didn’t plan for the cultural backlash of electing a black President and burn down our federal government and defunded our education and the transit infrastructure rather than our police and military state. Oh well… “you get the government we deserve,” said, Andres Duany once.

So here we are again in need of reforming our new urbanist, after-suburban sprawl, 20th century urbanist policies and regulations to be to meet today’s social demands. This zoning reform transitions from noxious industries co-location needs to regulating obnoxious neighbors sharing amenitized downtowns and sub-regional urban centers.

The following are a regional and citywide policy and econ dev framework for lot and block scaled zoning/regulatory reform:

Regional and Sub-Regional Urban Hotel (Transect Zones T6, T5, and T4-Neighborhood Centers)

Offers amenitized live, work, and play facilities for hyper-locals (new infill housing), locals (suburban commuters), and visitors (hotel business/pleasure). Dollars are flowing in from these types of citizen consumers.

Private Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Retail – Dining and Entertainment, and Shopping

– Daily Needs Services – Gym, spa, sundries, bodega, rentals

– Office Facilities

– Hotels (Long-Stay)

Conferencing Facilities

– Hotels (Short-Stay)

Pools, spas, gyms

– Homes – mix of uses (working and living)

– Paseos – Access between spaces and buildings

– Belvederes – Roof decks and garden terraces

– Parking Areas – Access to spaces and buildings

Public Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Conference Center

– Plazas/Squares – Destination civic space, active and contemplative

– Civic Services – Library, Post Office, City Hall, Pool

NGO Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Chamber of Commerce / Meeting Rooms and Facilities

Suburban Workshop (T4 General, and T3)

Offers live, work, and large-scale play facilities without amenities in existing suburban communities. These are static places with low-growth, and little change the appearance of the pods of housing or commercial or industrial. Auto-oriented but adding work from home and people wanting to walk around for exercise, post-pandemic.

Private Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Single-family Detached Homes

– Accessory Dwelling Units

– Yards

Public Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Ballfields

Regional Rural Substructure (T2)

A zoning conflict we’re addressing today are the regional infrastructure and utility issues bumping against either the suburbs or smaller, historic towns. Agriculture being the original regional utility/commerce.

Private Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Energy – Solar, wind, electrical (Efficiency Issues)

– Substations, powerlines (Wildfire Issues)

– Data Center Districts (The Next Big Deal to Deal with)

– Agriculture lands, Farmsteads, and Farm Worker Housing (Resort Districts)

Public Buildings and Spaces Functions

– Freeways, Highways, Corridors

– Federal and State Parks

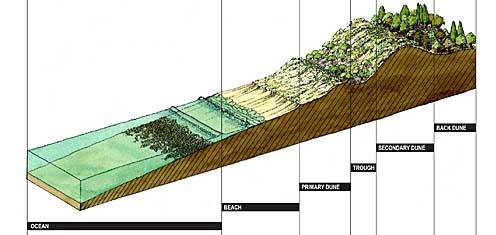

Preserved and Pristine Nature is T1