Offering urban design, planning, entitlement, coding reform, street design, facilitation, and placemaking expertise services for your development, neighborhood, or city. By blending timeless urban design techniques with innovative approaches to solve public or private client objectives, let’s work together to develop and implement a strategic plan that achieves, and exceeds, your goals.

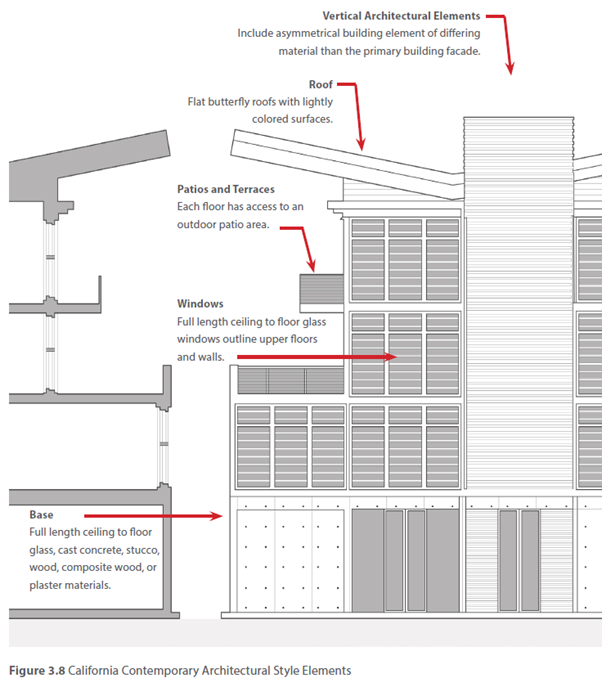

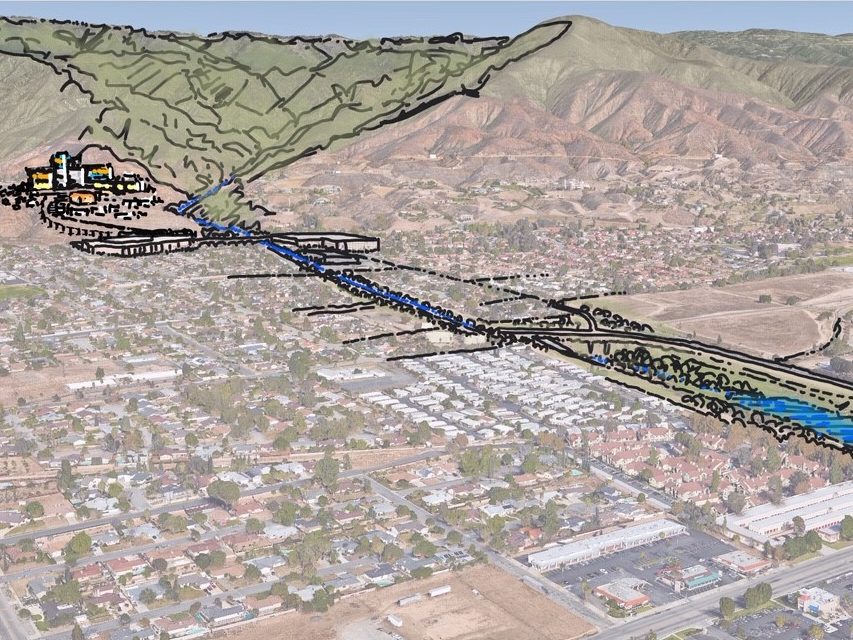

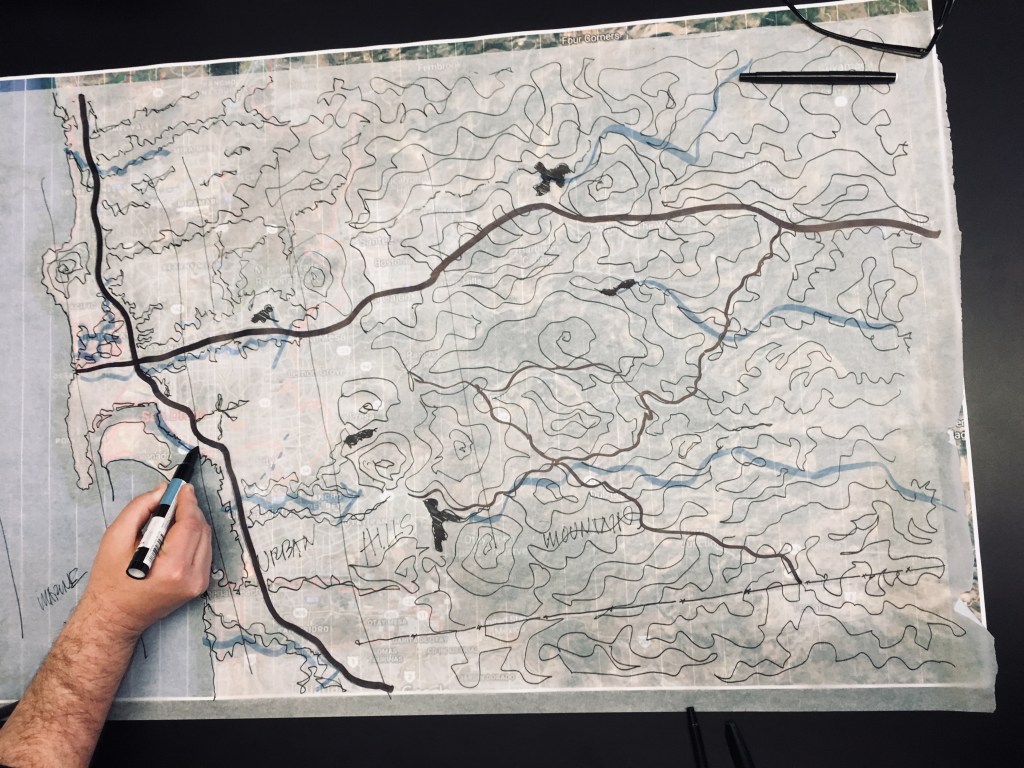

Designing for the Next Urbanism means to plan, design, entitle, and deliver places and spaces that people love. This means designing for a community’s actual ‘character,’ understanding that walkability does not end at the front door, and that code for and build’s 3-dimensional places. Innovative design and planning techniques include Live-Sketching Workshops, Coding for Character, and the Vertical Transect. These tools, in addition to place-proven mixed-use, walkable design techniques, add value to new or existing streets, parks, and buildings in places, towns, and cities of unique value within their region.

Balancing innovation with timeless design techniques provides private developers unique value to distinguish designs, plans, and codes from conventional, race-to-the-bottom competitors. In addition, entitlement navigation, public facilitation, and value-added placemaking interventions provide developers an advantage in today’s marketplace. With the ability to collaborate with nationally recognized specialist consulting firms from the regional to lot scale, the goal is to continue delivering comprehensive plans and entitlements that build successful places that people love.

The value provided to public municipalities and agencies comes from experience working on both sides of the counter as staff and consultant, as well as being an appointed decision-maker. Expertise in coding reform tools that include Objective Design Standards, Form-Based, Place-Based, and Context-Sensitive Codes, are transforming how cities build housing, transit corridors, and local businesses. We use a contemporary economic development approach to downtowns, suburban workshops (WFH + subregional centers), and rural regional infrastructure corridors (regional-scaled agriculture, energy, and data districts). This allows for a practical and sensible way of providing a place for everything with everything in its place in today’s economic reality.

As a certified public facilitator, I manage design-led charrettes and workshops using an innovative Live-Sketching tool to quickly visualize public feedback and build consensus. And I uniquely am able to combine creative design skills with technical coding expertise and then clearly explain both to stakeholders and citizens.