My most significant educational experience was sitting directly across from Leon on a 5-day charrette in Chico, California, 22 years ago. The intense time spent with him changed the trajectory of my professional life… because Leon Krier was right.

“Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free.” – Jesus

Leon was a man of great character, who was the largest influencer of my education, as far as any single person could have affected it. Another iconic person (of whom I can never repay for their professional generosity and genius), Andres Duany, wrote this loving eulogy that correctly identifies the voracious and tenacious conviction of Krier’s work in contrast to Leon’s gracious, admirable, and courteous lifestyle. His life’s story is well documented. His uniquely lived experience of growing up in Post-WWII reconstruction Luxembourg, combined with his informal education (he learned from mentors and teaching at London’s Architects Association) as processed through his complex character (see Duany’s description above) shaped his incredible creativity.

Leon correctly identified that industrialization had devastated our civilization and its buildings and cities. Krier was the first to challenge the modernist dogma in the 70s as young architect. Because of his lone advocacy turning into a movement, today we have a fuller spectrum of design choices, from self-referential modernism to traditional vernacular to classically ordered tools. Leon Krier was right.

A few years ago, upon picking him up from the airport, I immediately drove Leon to share my disdain of the latest modernist infill project in my turn-of-the-century streetcar neighborhood. It’s a copy of Corbu’s Villa Savoye that had been in Architecture Record. I was fully expecting an affirmation of my disgust when Leon surprising said, “It’s good.” My eyes widened and my hands gesticulated wildly as I explained that the building’s fenestration was backwards, completely ignored its context, and the urbanism only existent in materials and scale. Leon agreed that while all I said was true, for a modernist building it was a very good example.

The lesson being, “If you are going to do modernism (or anything for that matter)… then do it well.”

I had forgotten how difficult it is to get any building or nice place built. My New Urbanist dogma had gotten in the way of this human truth. He said that to build anything in today’s toxic environment (naturally and politically) was laudable and then to build it well was meaningful. Leon Krier was right.

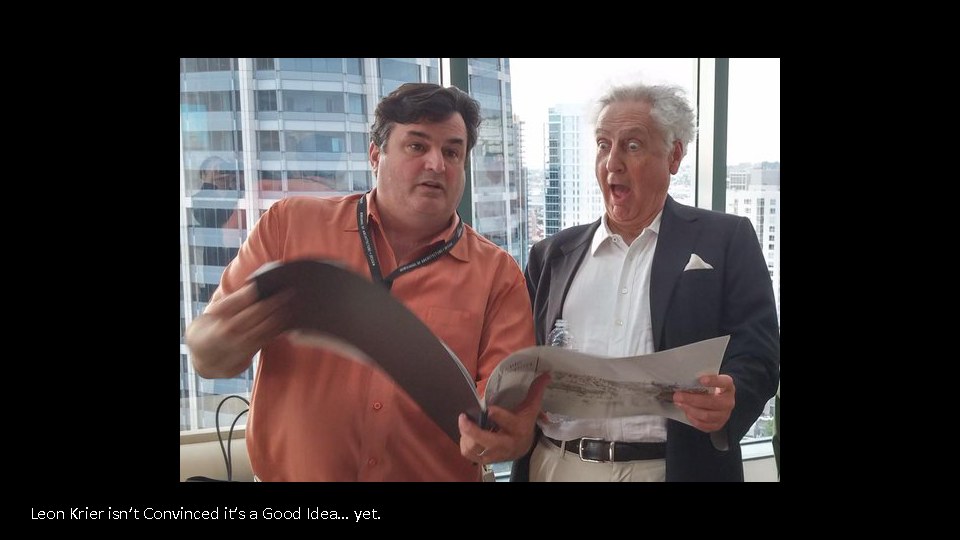

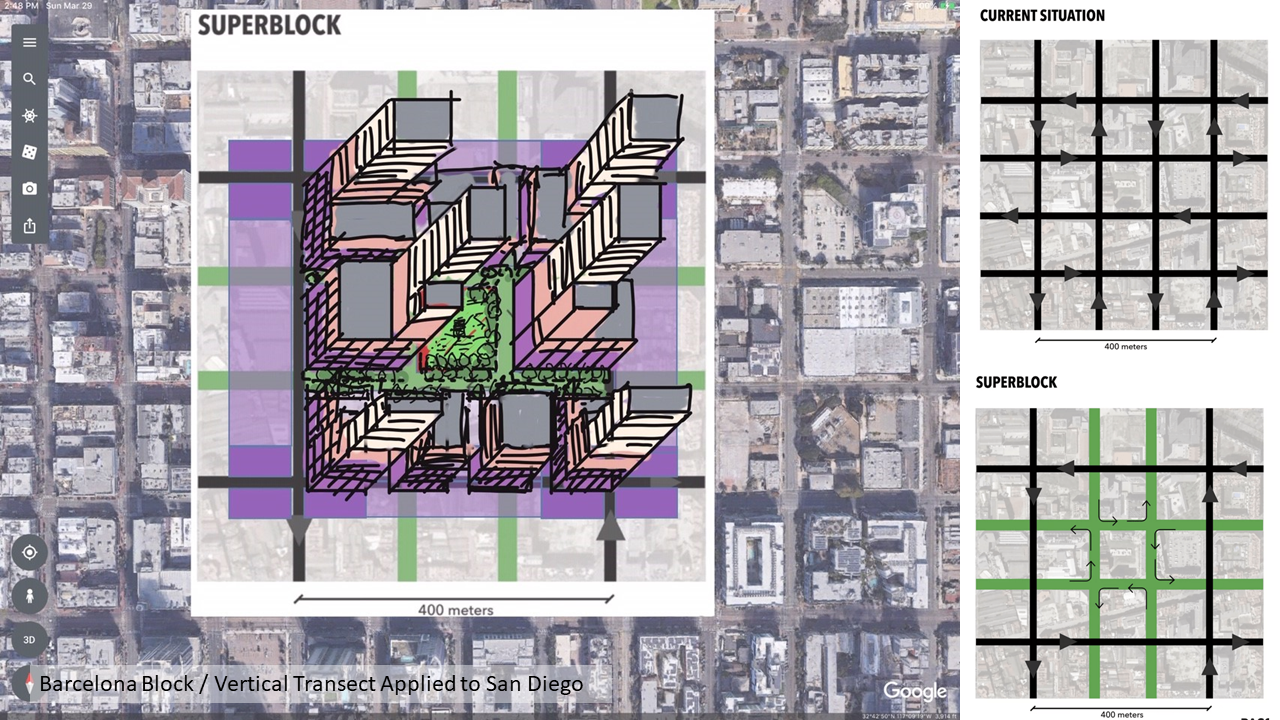

I am fortunate to have spent days and hours talking with Leon while driving across US west deserts, working in San Diego, and online during Covid. While his professional works is polemic and absolute, his personal perspective was equally optimistic and positive. Another grand lesson I learned from Leon on the importance of what we do was that, “The architecture the city and public spaces is a matter of common concern to the same degree as laws and language; they are the foundation of civility and civilization.”

It was a feast to have learned these truths from my genial mentor. Thank you again, Leon.

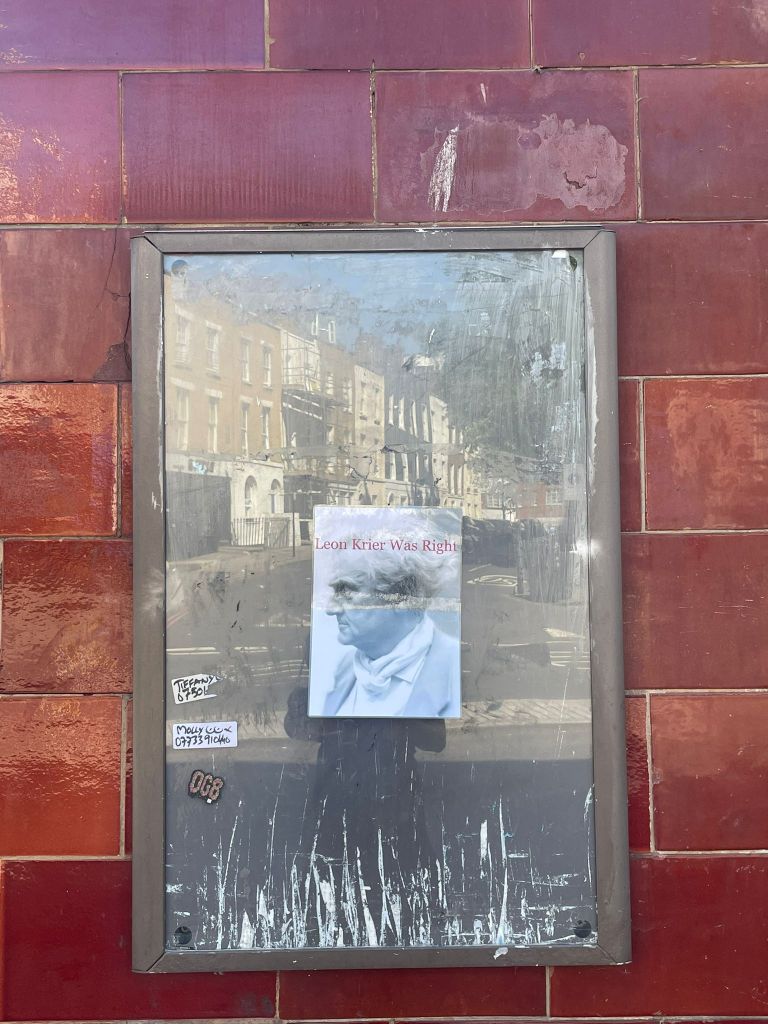

[This week my lovely daughter in London posted this in front of the Architectural Association]