How can communities plan to become more adaptable and resilient in the face of climate calamities, such as wildfires, hurricanes, drought, heat waves, and floods? One idea is to start with an audit. Using Jeff Speck’s successful 10-part “walkability plan” as a template, I wrote a list of steps that a community could use for a “climate adaptation audit.”

The 10 steps below are grounded in the principles of New Urbanism, which are based on the design of cities and towns that have survived for centuries. Compact, walkable places are more resilient, but they also need to respond to modern conditions and the science of climate change.

The ten audit points aim to give towns and neighborhoods a chance to make living on earth attractive to a broader range of people. These are all applicable to any location, and a community that checks all of these boxes should be “climate calamity ready.” Using this audit, residents can see what they need to prepare for and how to align resources.

- Inform the public of climate adaptation activities, encourage citizens to become involved in the planning process, and engage in broader professional discussions and information at local, national, and international levels.

- Understand your local context’s climate risks to be used as baseline data for a Climate Adaptation plan (use the Place Initiative tools Community Assessment Guide).

- Determine local consensus on a long-term vision, choosing to either permanently retreat, temporarily evacuate, and/or harden against climate calamities. Facilitate cooperation among citizens, public interest groups, non-governmental organizations, and governmental agencies to shepherd plans and policies toward envisioned outcomes (to retreat, evacuate, or harden from/against weather/fire/water/earth).

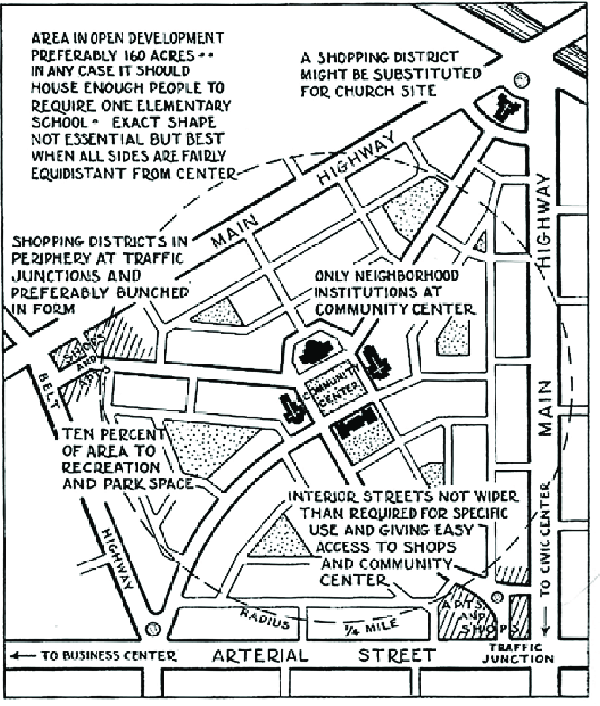

- Apply New Urbanism’s best practices to determine if new/future development is best directed in the form of infill, town extension, and/or a new town to shape continual development at a human-scale in response to the region’s changing social and economic needs. (Diagramming new urbanist principles, outcomes, and results is needed to improve calamity resiliency).

- Enable place-based policies, standards, guidelines, and plans that employ the highest standards of New Urbanism best practices (mixed-use, walkable, transit-supported) urban design and planning to define and advance the local municipality’s interest in long-term social and economic viability.

- Set a by-right approval process in place for projects and applications for approval that are consistent with civic policies and interests (a non-discretionary approval process reduces the power of bad actors to reject projects that address climate resiliency).

- Set a straightforward discretionary review process for proposals and applications that are subject to council or supervisor approval to determine whether they are consistent with the civic policies and interests.

- If retreat or evacuation from identified climate calamities is required, determine the type of calamity, its context, emergency routes, destinations (and alternatives), and who is responsible (fire marshal, city manager/mayor). For example, if there is a wildfire in a mountain context, with clear (lighted/reflective) signage for routes to safety (state highways, local roadways), and design the route for this climax condition, such as fire truck access and directional lane adjustments.

- If hardening from climate calamities, identify the type of calamity, its context, types of response (and alternatives), and who is responsible (building and development services manager). For example, if there is a wildfire in a mountainous area, build with fire-safe codes, with overlapping zones of defense around clustered compounds, allowing for firefighting from the roadway. Make space for wildland firefighting (no new sprawl) and structure firefighting in clustered compounds. Do the same for flooding, sea level rise, and extreme weather conditions (See Martin Dreiling’s 2010 Fire Mitigation in the Wildland Urban Interface SmartCode module).

- Choose a capital Improvement Plan that prioritizes the path of least resistance to determine where spending the least money would make the most difference and build from there. For example, fund, maintain, and operate tactical “communication command control centers” to be deployed immediately for disaster recovery.

While communities have been planning for climate resilience for some time, the idea of a step-by-step audit grounded in sound urban principles makes a great deal of sense. Please let me know your thoughts.

Note: A recent CNU webinar on “Climate-ready communities” discussed state and provincial policies and tools. The author, an attendee, suggested the “climate adaptation audit” tool, and it generated interest.