I begin a project by reading and listening to citizens, existing policy-documents, and experts in an area. Learning the issues and background information, or due diligence (now called data gathering), is the first step in generating ideas. My design biases are found in my appreciation for John Cleese’s creativity approach by being open minded with play to envision scenarios and closed minded to then focus on the design product afterwards. As well as my personal design process fitting within the spectrum of life… between life to death, night to day, light to dark, man to woman, formal to informal, yen to yang, etc… as an inherent basis for my design approach. And this third tool is to figure out where the place sits is more urban or more rural spectrum today and where it’s going in the next 5-10 years and then beyond.

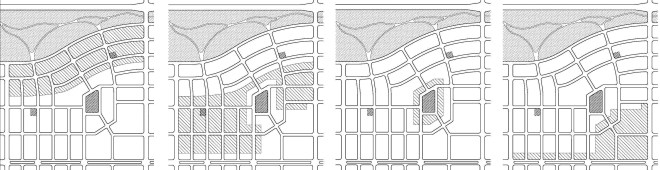

Fourth, I begin designing (usually on an iPad/Morpholio Trace program) applying a variety of street, parks, and building types, from most intense to least intense, that explicitly guides new building towards a distinctive “character and sense” of place. See Leon Krier’s idea of how to coding for a specific community character here (note: there are only 16 character types). So using background info, my biases, and multiple street/park/building types tools… I then take an outside-of-the-box approach, looking at the surrounding context to identify public and private buildings and space patterns in the project area. These patterns are interdependent and shape the surrounding neighborhood characteristics. Identifying, understanding, and drawing inspiration from these patterns upfront allows me to address common issues raised in the first step.

Then I design within the project area with an inside-of-the-box approach, identifying these surrounding patterns within the design to coordinate the precise location of uses, buildings, spaces, services, and utilities with a focus on long-term social, environmental, and economic outcomes. Using these various patterns to identify a variety of buildings and spaces guides me to making design decisions that are either ‘in tune’ with its surroundings or it ‘stands out’ and accentuates a space or building. The design either blends in and fits harmonious with its surrounding patterns or its disrupts and breaks the patterns.

The combination of these approaches and techniques allow me to quickly make design decisions to create a specific character and sense of place, rather than leaving it up to chance… and the final design produces a new idea for a place that either respectfully fits within or distinguishably stands out from its local setting. With this start, I work again with local citizens, who have a unique understanding and knowledge of their communities, to gauge if their neighboring buildings, parks, and streets should stand out or fit in.

Local identity is a key in creating spaces that nurture community identity, instill pride, and positively energize communities. And I advocate for elevating the role of “good” design to a region’s public agencies, county, cities, advocacy groups, private organizations, and community groups, understanding that well-designed places are a practical and essential way to bring vitality and dignity to city living.

At the human scale, good design makes a difference in our lives by helping us feel safe and comfortable while walking and socializing in our neighborhoods, which helps us feel happier and experience a deeper sense of belonging to places and people.

And, at the city scale, good design makes a difference in enabling cities to attract and retain residents and businesses with inviting public streets, civic spaces, and interesting places more easily.

Ultimately, belonging to a place, and a home, is the idea that goes to the heart of what makes neighborhoods great. It roots our approach to urban design in respect. Respect for people and places, and a respect for tradition. It gives the fancy innovations and clever deconstructions a heart and a soul. An innovation is something new, something novel, maybe even revolutionary. But there’s another truth that’s deeply applicable to design, oftentimes the best innovations are ones in which a twist was put on something that has been done before.

What do you think?