Missing middle housing, and similar ideas of gentle density and incremental housing, are useful tools for cities allow for new homes to be built in existing neighborhoods. This is especially true for older or historic neighborhoods with predominantly low scale, low density, single-family detached homes. These are measured tools that transition long-standing neighborhoods from no-growth to adding more middle/medium scale housing/density/population. These new apartments/attached buildings adds a variety of people at different socioeconomic points of their lives, which smaller and larger units on the same neighborhood block tend to do. And new infill homes add tax revenues to fix old streets, sidewalks, lights, parks, and other civic infrastructure (in concept).

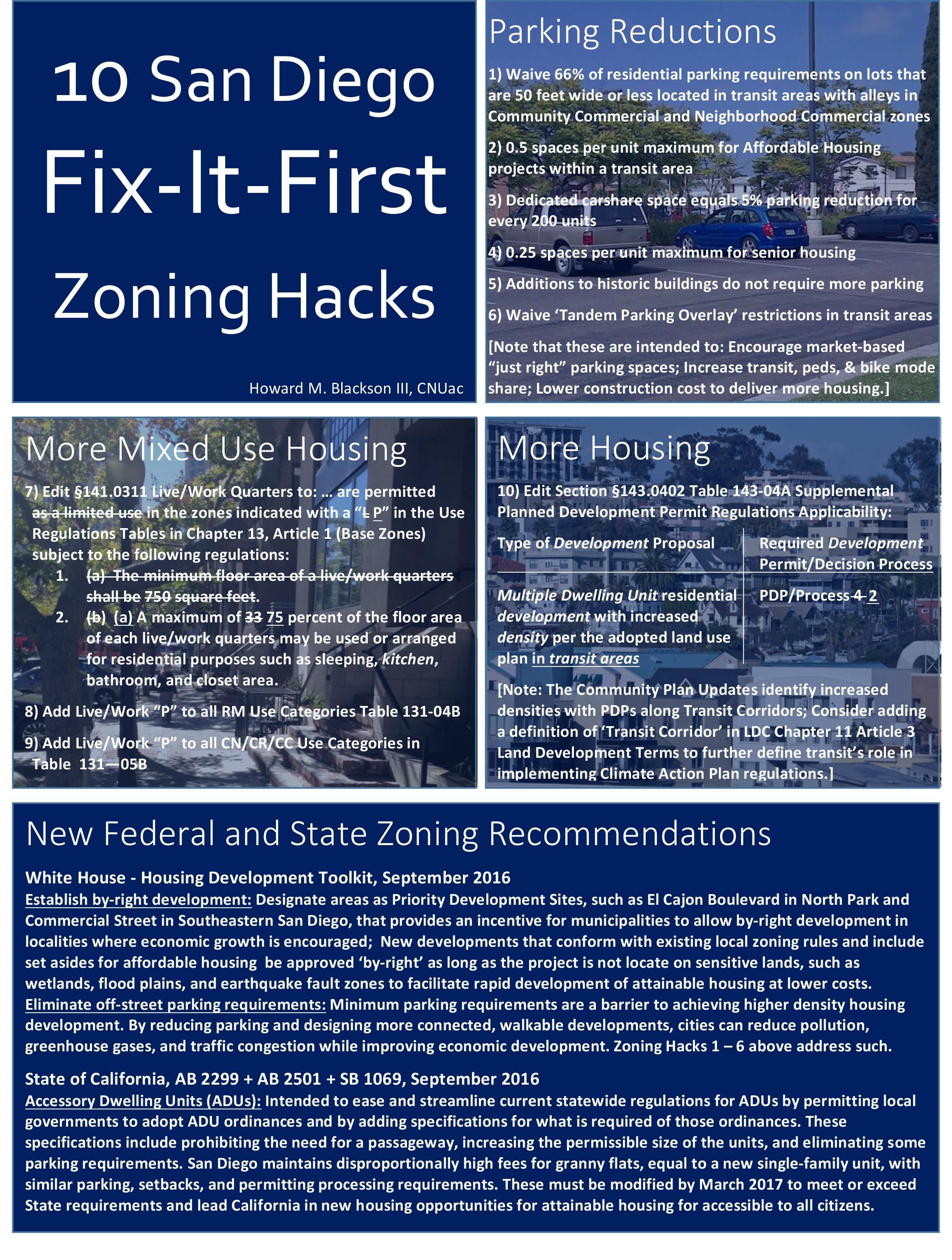

Fortunately the City San Diego’s planning department is starting to reform its zoning. It recently identified and adopted Transit Priority and Sustainable Development Areas. These allow for new projects that include affordable housing to waive its zoning, such as height, setbacks, and density. This is a very smart understanding that our city’s conventional zoning, the rules that regulate the configuration and orientation of a building, are out-of-date and not aligned with today’s housing-at-all-cost priorities. This is a great first step in recognizing that conventional zoning is broken. And for the past decade our state legislature has been pushing cities to allow for more housing and bypass its long-standing zoning rules, which have been rightfully deemed as being in the way of building cheaper, faster housing.

Born from racism and modernism in response to the industrial age, conventional planning and zoning is just a dumb form of segregation by land use. Residential, commercial, and industrial use separation has wasted our time (too many hearings, decision-makers, and gatekeepers), space (suburbia as far as the eye can see), and money (housing scarcity and prices). It is has been in need of reform for decades, but status quo is difficult to change, as well as messing with people’s inherent land values.

As a New Urbanist, I’ve been advocating for Form-Based Codes as code reform for over 25 years. These emphasize the configuration of buildings and places in context and/or form first, such as Main Street buildings on Main Street and rural buildings in rural areas. The function, or land use, of a building and its surroundings, are of a lower priority in Form-Based Codes as mixed-use, walkable urbanism is more complex than making us drive to a pod of work/home/play/shop/worship suburbanism. It is a proactive, rather than restrictive, approach to zoning regulations. And Form-Based Codes (now Objective Design Standards in California) are reforming zoning across the nation, albeit slowly.

Thankfully, the New Urbanism has won the war against suburbia. New housing is mostly in town or extending the town’s boundary on its edge. Rarely do we build new stand-alone subdivisions out by the wastewater plant, over ancient graves, or adjacent to heavy industrial districts, which is a good thing as those are noxious and dangerous places. Today these noxious districts are regulated by State or Federal rules and not local municipal zoning anymore. However, the new Federal administration is pulling the plug on these regulators, so…

Wiser, I see that new housing isn’t being located near those old toxic/noxious places, such as iron smelting or horse melting to make glue – as those industries are now done in other countries – because new homes are mostly being built next to existing homes. This means new housing problems are how their presence creates friction between both new neighbors and with existing residents. In short, as much as we love people and each other… we also really don’t like each other just as much. We live in a world wanting peace and quiet, and rules to keep it that way (see: every religion).

As humans, we understand that we have more public fronts/faces, sides, and more private rears/backyards. We prefer people, that aren’t immediate family, to either face us along a more formal public street or back onto each other with private space/yard or messy service alley. We’re built this way. It is well understood, comfortable, stable, and peaceful. Especially when we respect our western cultural social and physical norms. Bravo’s housewives, “Be cool, don’t be like all uncool,” would probably be a great zoning reform policy.

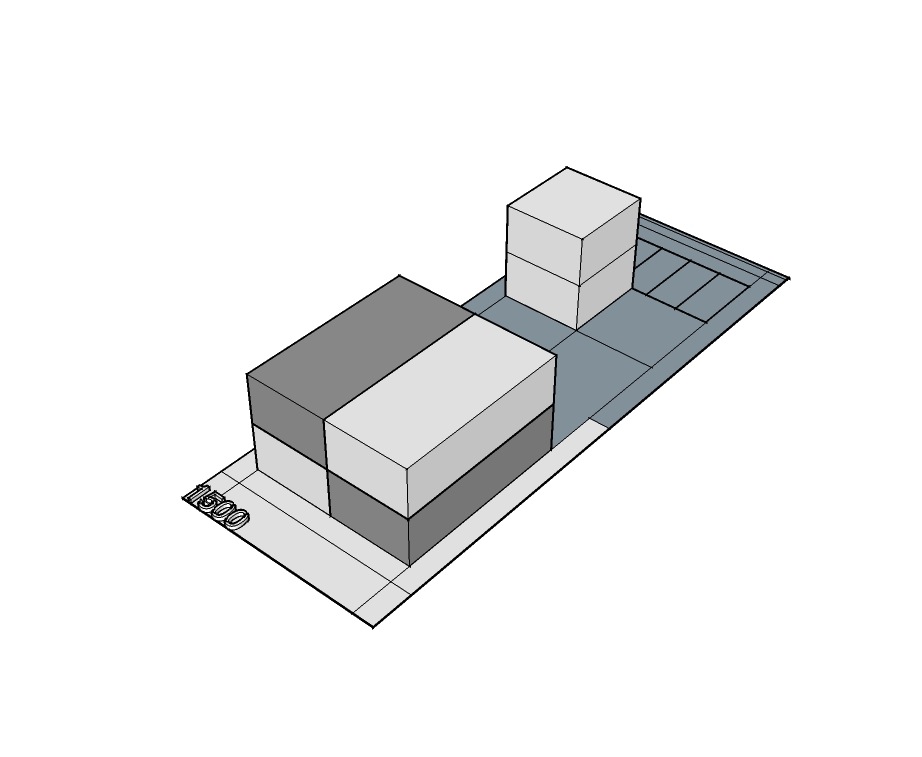

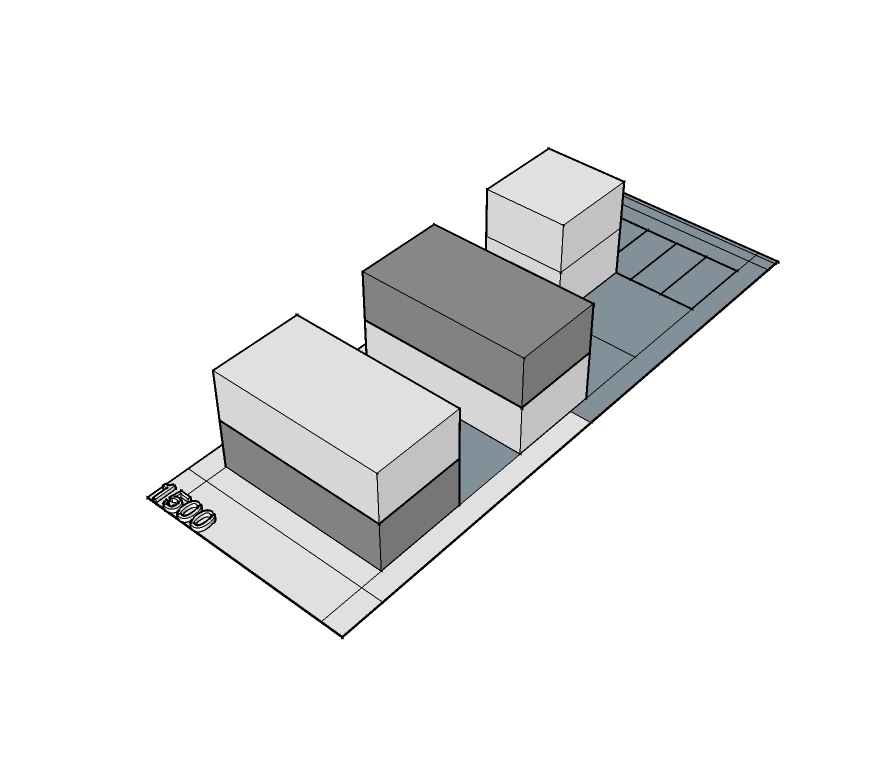

We also want justice. And when someone else appears to be getting ‘more’ than ourselves or others, it creates a sense of injustice. When one neighbor places a 3x taller building next to low-rise homes, it confuses the home’s fronts and backs as well as land values, which are destabilized with extreme building types sitting adjacent to each other. It creates fiction and conflict between people, not the land uses.

Without building zoning standards, public fronts and private backs are confused. Where are we supposed to be loud, welcome guests at the front door, throw our trash, sit quietly, and put screaming kids to play? Being cool is more than a suggestion… it’s in need of new rules.

Zoning today equates to almost exclusively dealing with obnoxiousness between residents, such front doors looming over backyards and quiet places versus public engagement places. These aren’t noxious issues, such as industry pollution spoiling the land, but more offensive social issues that spoil our previously suburban quality of life (more on that in a later blog), as the want for quiet and dogs/pets in downtowns are a “suburban echo,” and a new expectation for living in urban neighborhoods. Zoning reform needs to focus on these very real issues. The absences of rules only creates unintended conflicts between neighbors.

We need to set boundaries on how to live together. Meaning, we need new zoning rules for obnoxious behaviors rather than 1940 rules for noxious conditions. Sociable neighborhoods start with putting the right range of building types on specific street types with specific park types that help our society get along well. Missing middle housing types are better than towers to fill in older neighborhoods. They create less conflicts while adding lighter, faster, and cheaper homes.

These are simple rules that can be monitored by city (public) planning and development departments while it works towards building better public streets, sidewalks, lights, and parks (public entities doing public stuff), while regulating the simple stuff that we know lends itself to obnoxious behaviors between private developments. Following any good planning strategy, zoning reform starts with understanding today’s context, collaborating to generate a common Vision (making policies that relate to our values and priorities today), then generating a plan and/or code (making regulations), and then making them happen through actions and implement is how we implement zoning reform today. Be cool.